Assessing the Future of Latin America’s Major Economic Power DynamicsAssessing the Future of Latin America’s Major Economic Power Dynamics

During the second half of the 20th century, Latin America experienced prominent political and economic volatility, slow economic growth, and a myriad of security threats that affected the region unevenly. This mixture of variables delayed the capacity of the Latin American regimes to engage in a post-war industrialization period led mainly by Europe and followed by countries such as Japan, Singapore, Korea, Hong Kong, or China. Over time, and due to the increasing number of far-left regimes fueled by the 2000 Latin America commodity boom, the region’s countries rapidly fragmented, following different ideologies that produced devastating effects in some cases.

During the last two decades, the region’s economic and political landscape has changed dramatically. On the one hand, economies formerly recognized as nodes of economic development such as Venezuela, rapidly muted into a bizarre version of tropical communism, enduring long-term hyper-inflationary periods and exodus only comparable with those suffered by Europe during World War II. By 2020, the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) (1) estimated 5.4 million refugees and migrants from Venezuela with an 8,000 percent increase in the number of Venezuelans seeking refugee status worldwide since 2014 (2). In contrast, a country like Peru, being one of the poorest of the region, has been able to quadruple their PIB Per capita since the 80s, with expected economic growth above 5 percent for the upcoming five years (3).

As a preliminary caveat, in some cases, the real size and capabilities of different Latin American economies are distorted due to the increasing size of criminal organizations, and particularly narco-traffic groups, some of which have their main territorial dominance in Colombia, Mexico, Peru, Venezuela, Brazil, and Bolivia. Since the late 70s, the economic assessments of these countries have often ignored the size and influence of illegal flows of capital. For instance, drug trafficking in the Colombian economy has weighted up to 3.5 percent of the GDP, becoming a source of last resource liquidity amid recession or deflationary trends (4). This phenomenon has allowed certain communities and regions to engage in fictional or bubble economics where small but potent illegal organizations can distort the markets, leaving behind inflationary pressures endured by the lowest segments of the population.

This background makes it difficult to assess the real stage of development of the Latin American economies, eroding the possibility of addressing the stage of a permanent economic contest between countries in the region. Moreover, these settings reorient the commercial and political interests of the countries from the outside to the inner domestic urgencies derived from the social, cultural, and political constitution of each nation. However, in recent years, the region has experienced economic and political events that can split the economic landscape for the years to come, where highly state-owned economic systems aim to challenge market economies eager to provide goods and services for the region and the rest of the world.

The region’s economic fragmentation

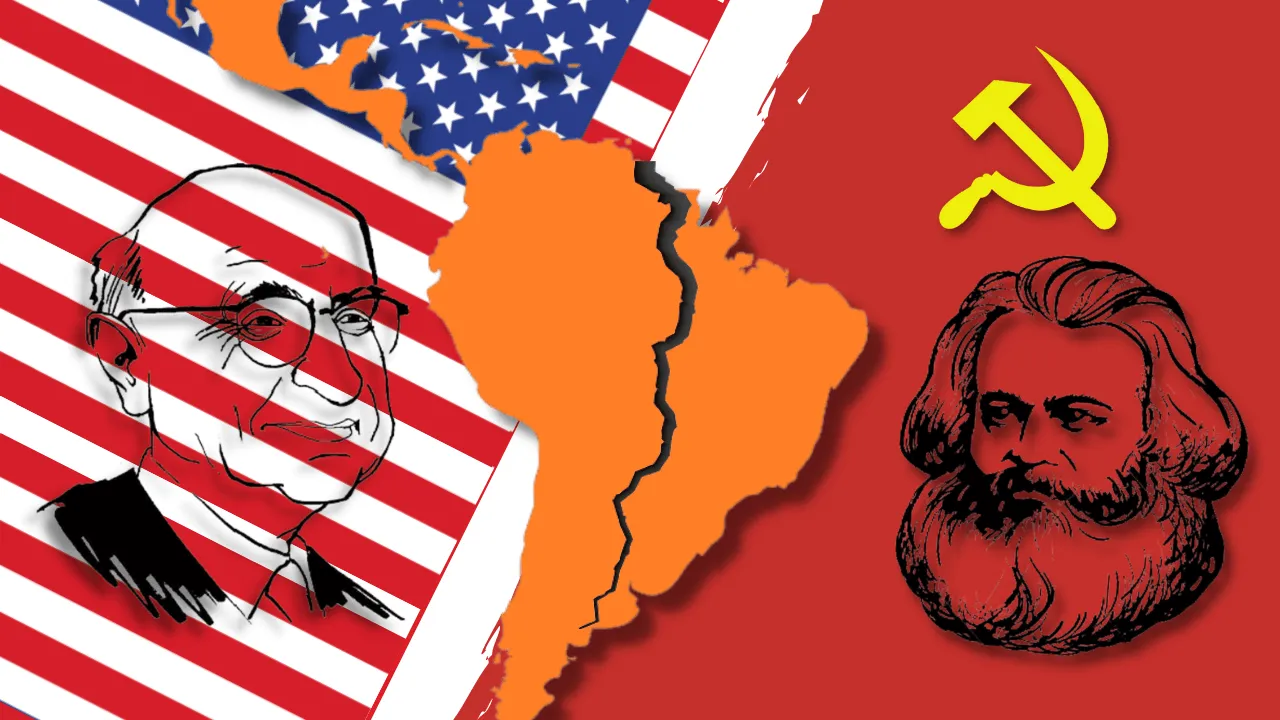

Over the second half of the 20th century, Cuba’s influence in the Latin American region slowly diverted the regional culture into an ideological battlefield. The strong influence of communist ideas rapidly colonized marginalized or poor populations of the early market economies, becoming a device of social discontent boosted by the polarizing interests of the United States and the former Soviet Union (5). This historical background served as the cornerstone of Latin America’s political systems, often unable to steer cultural and social differences while developing market economies in an unstable political environment. The 2000 Latin American commodity boom served as the tipping point of the ideological trends that erupted early in the Cold War. The large-scale spending of the Venezuelan regime of 1999, led by Hugo Chavez, rapidly fueled the political power of far-left political parties all over the region, turning Latin America into a region of trans-hemispheric strategy (6). This phenomenon increased social tensions between the rich and the poor sharply, helping the arrival of neo-communist regimes in Nicaragua, Bolivia, Venezuela, and Argentina, and notable cases of state interventionism in Brazil, Paraguay, and Colombia. (7) Latin America’s economic landscape changed dramatically, divided into a mixture of weak market economies on the one side and state-owned economies on the other.